Rutgers-Newark Conference Explores How to Spur Equitable Growth in Cities

An event hosted by Rutgers-Newark’s Center on Law, inequality and Metropolitan Equity (CLiME) explored how to shape cities that are thriving and affordable for all residents, despite a long history of federal and state policies that have made it difficult to avoid displacement and gentrification.

The “Equitable Growth in the City” conference held last month at Rutgers Law School in Newark convened scholars, private sector leaders and public officials to focus on the creation of affordable housing and community resources through redevelopment.

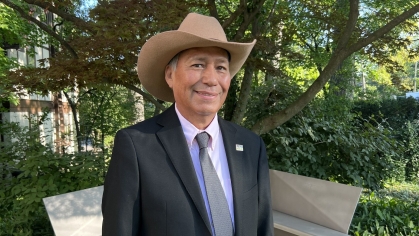

Newark Mayor Ras Baraka, who gave the event’s keynote speech, described how colleges and universities can improve lives in cities where they are located by leveraging their potential to spur inclusive economic growth and research collaborations with residents and local government, as CLiME has done.

He praised the work of Rutgers-Newark Chancellor Nancy Cantor, who stepped into her role in 2014 and will leave next month to become president of Hunter College and whose leadership has been dedicated to the university’s role as an anchor institution.

“She understands the public nature of a university, its resources and the impact it has on the overall superstructure. She makes the university useful in a multitude of ways,’’ said Baraka. “She understands that academia works best in full public view, not to just point out a problem and make pronouncements about it. Its candor and clamor should be felt outside university walls.’’

CLiME has published several reports focused on affordable housing and land use in Newark and neighboring Essex County cities, such as Irvington and East Orange. Its data collection and recommendations have informed municipal redevelopment plans and regulations.

At the conference, CLiME fellow Elana Simon, who is earning her doctorate at the University of Southern California’s Price School of Public Policy, presented the center’s latest report, titled ”Empowering Public Property,’’ which she co-authored with CLiME Director David Troutt.

It outlines recommendations for how city-owned property can be used to add 2,500 units of affordable housing, cultivate more green space, and develop commercial space for local business owners and entrepreneurs to create jobs. It also offered suggestions for using public property to make healthcare services and healthier food more accessible.

In a panel called “Challenges Behind Affordable Housing Innovation,’’ participants shed light on policies and practices that exacerbate the housing crisis and proposed solutions.

Troutt introduced panelist Adenah Bayoh, one of only a handful of Black women developers in New Jersey, as an example of someone who has found creative ways of changing the housing industry.

“She represents the best of the entrepreneurial spirit in thinking about community change and the way capitalism can be used more compassionately and effectively to achieve the goals of an equitable city,’’ he said.

Last year, Bayoh, an Essex County developer, became the first woman-owned and Black-owned real estate development entity in New Jersey to receive a 9 percent Low Income Housing Tax Credit to build the affordable housing complex, Southside View, in Newark’s South Ward.

The 40-unit multifamily complex will provide tenants with paid internet for 15 years, laptops for children, free tutoring, and access to a computer lab and social services programs.

Bayoh gave a presentation that highlighted inequities and outmoded regulations in the housing industry, including those which govern who qualifies for affordable housing.

In highly stratified Essex County, which includes wealthy suburbs like Short Hills and Livingston, along with cities and towns where many residents are low-income, the criteria for what’s considered affordable is based on the county’s median income instead of a town-by-town calculation.

The median income of renters in Newark is $30,000, said Bayoh but the average rent in the city is $1,507. Housing that’s considered affordable is $1,100, which is out of reach for many.

“Newark renters should not pay more than $871 to keep them out of poverty,’’ said Bayoh.

A barrier for many who seek to build affordable housing is lots that are zoned for single family homes, regulations that contribute to segregated communities, especially in New Jersey, where 64 percent of white households own homes, while only 40 percent of Black and Latino households are homeowners. “It’s probably the most racist instrument designed by our government to keep people out of certain communities,’’ said Bayoh.

Bayoh pointed out the disparities between the demographics of public housing tenants and the demographics of developers, who are overwhelmingly white men.

“One in every 1,200 developers is a woman of color,’’ she said. “But 71 percent of renters who live in affordable housing are minority and 75 percent are single mothers.’’

Also on the panel was Alan Mallach, a senior fellow for the Center for Community Progress, who proposed that entitlement programs for housing could help solve the housing crisis. “If you can’t afford food and meet the criteria, you can get SNAP benefits. But if you need housing it’s like buying a lottery ticket. Maybe you’ll get lucky. Anyone involved in advocacy should be pushing for that. It’s far more important than the allocation of low income tax credits. It’s more important than any other single housing strategy,’’ he said.

Several CLiME research fellows presented their findings at the conference, including

Mussab Ali, who gave a presentation on gentrification dynamics in three New Jersey cities.

Anna Griffith gave a talk on modeling legislation to curb institutional buyers while Joshua Miller spoke about lost opportunities to promote community policing. Steve Northington presented research on economic disparities in transportation planning and Kay Rogan explored designing houses for health.